Monument Lab Live "Hidden Histories and Missing Monuments": A Reflection

Cynthia Heider | 5 November, 2017

Reflect on history. Imagine the future. Change the present.

-Monument Lab tagline

Images, from left to right: Tania Bruguera's "A Monument to New Immigrants" installation at PAFA; Prototypes of proposed monuments for the city of Philadelphia on display at PAFA; Close-up of proposed monument prototype. Author's photos.

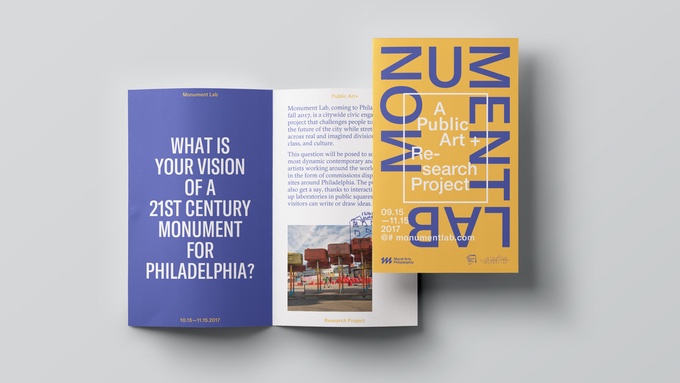

It’s taken me about three weeks to gather my thoughts about the Monument Lab program that I attended at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, entitled “Monument Lab Live: Hidden Histories and Missing Monuments.” This was the first event I’d been able to make it out to, although I first heard about Monument Lab back in June, contributed to the Kickstarter fundraising campaign, and shared my excitement with others via various social media platforms.

To give some background for the unfamiliar, Monument Lab is a “public art and history project” sponsored by Mural Arts in Philadelphia. The project, five years in the making, is intended to spur a “citywide conversation about history, memory, and our collective future.”[1] To do this, the project’s curators solicited ideas from the public about their wishes for the monumental landscape, and commissioned dozens of artists to place temporary “monumental” art installations around the city from September 16th to November 19, 2017.

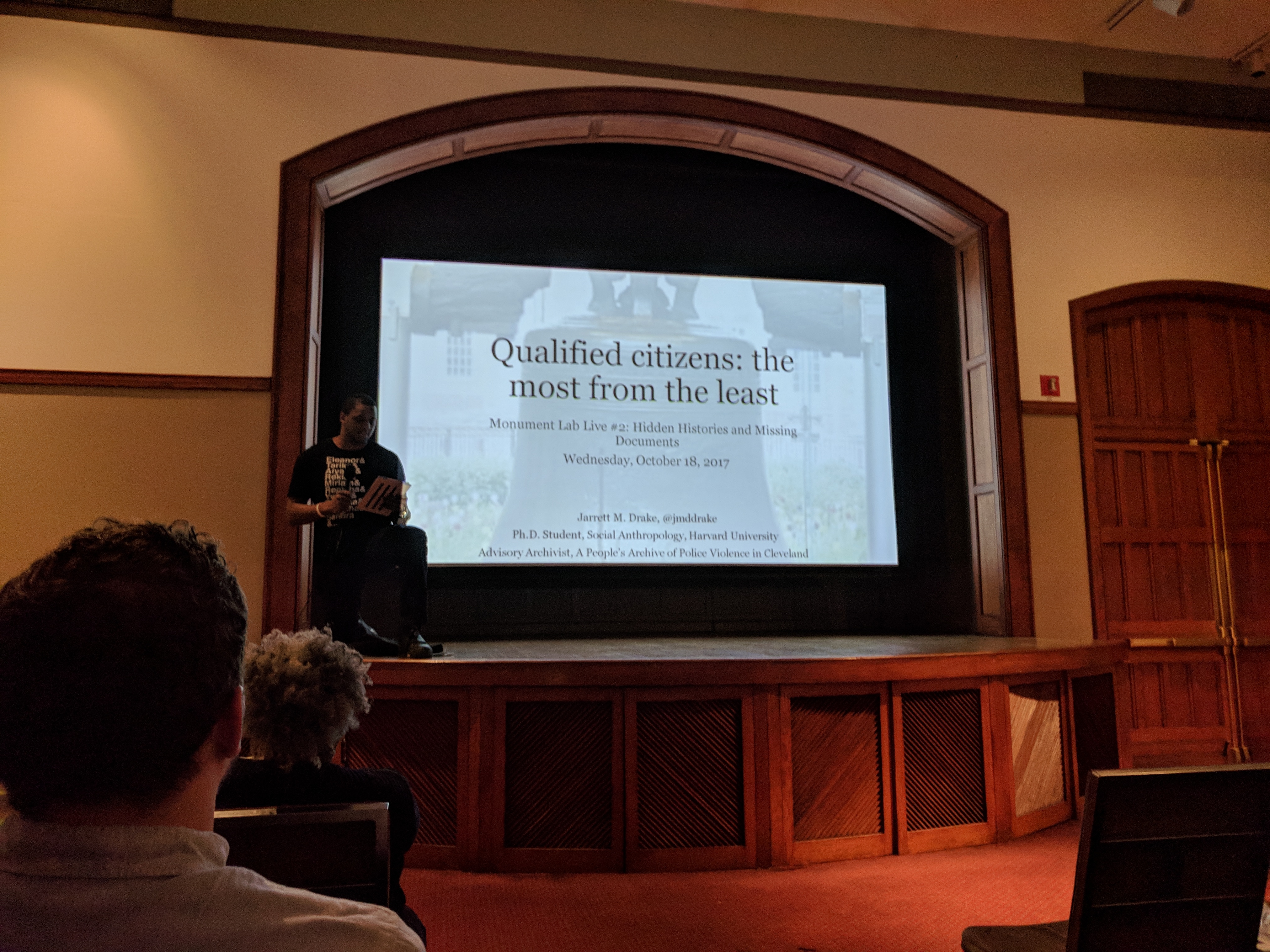

“Hidden Histories and Missing Monuments” was powerful, topical, and packed to the gills with engaging and passionate speakers. The event featured a slew of inspiring presenters, including Vashti Dubois of Philadelphia’s The Colored Girls Museum; Brian C. Lee and Sue Mobley of New Orlean’s Paper Monuments (a sister project to Monument Lab); artists Venissa Santí, Marisa Williamson, and Kaitlin Pomerantz; and archivist/activist extraordinaire Jarrett M. Drake.

Jarrett M. Drake is my archives rockstar. He’s a great example of the impact an individual devoted to thoughtfully confronting the problems of archival silence can make in both theory and in practice. He intrepidly, intelligently, and empathetically questions the ways in which power structures and prejudice serve to elevate white, middle-to-upper class voices in the archival record at the expense of preserving histories of the societally marginalized, regularly contributing to Twitter hashtags like #ArchivesforBlackLives and #ArchivesSoWhite. He’s been involved with the People’s Archives of Police Violence, was Princeton’s first digital archivist, and when presented with boilerplate interview questions, gives amazing answers like this:

At “Hidden Histories and Missing Monuments,” Drake once again addressed the issue of silences, both archival and in the public landscape, delivered on bended knee in recognition of the silences surrounding violence against Black girls and women. Recognizing a contradiction of American self-conception in the difficult histories he has come upon preserved in the archive (like judicial and legal collusion to enslave and traffic American citizens in the early 19th century), Drake argued: “I contend that Philadelphia, like any self-proclaimed free society, should construct memory sites for peoples whose experiences of exclusion, exploitation, or enslavement contradict that society s common conception of itself. I urge this consideration because a free society will learn the most about itself by confronting its treatment of the least.“[2]

Following the event I found myself awed. “Wow!” I thought, “this is exactly why I study what I do!” Marginalization in the historical record is an insidious and devastating process. It was inspiring to see archivists, historians, artists, and activists working together to not only draw attention to the problem, but brainstorming how to solve it in innovative and publicly-engaging ways.

Images: Bryan C. Lee and Sue Mobley discuss the Paper Monuments project; An example of a proposed Paper Monument project

Images: Marisa Williamson introduces her interactive "Sweet Chariot" application; The scratch-off accompaniment to the scavenger hunt of "Sweet Chariot". Author's photos.

But as the weeks trickled by, and I redrafted this blog post at least three times, I began to realize the concurrent feelings of disappointment and frustration holding me back from hitting “Publish…” I’d been stricken and confused by the relative smallness of the event’s audience, especially given the immediate topicality and weightiness of the issues addressed by the speakers. Why wasn’t it held at a bigger venue? Why wasn’t it more heavily promoted? Should I read into these things as examples of marginalization?

But this wasn’t the first time I’d noticed this particular issue in relation to Monument Lab. Since my involvement with the Kickstarter began early in the summer, I’ve noted with surprise that no one I have mentioned Monument Lab to within the Philadelphia area has been aware of or engaged with the season-long project; this has included artists, public historians, and people much more closely attuned to the beating heart of the city’s cultural scene than I can claim to be. Even at the beginning, the fundraising stalled several times and it seemed that the fundraiser might not reach its goal. In the end, somewhere around 430 people contributed to the campaign (about .03% of the population of Philadelphia) and the rest of the funds were provided by large-scale backers. It struck me at the time that Monument Lab might have some promotional issues to contend with, an impression that was confirmed in my mind by the “Monument Lab Live” event’s relatively low profile.

Philadelphia’s conversation surrounding the city’s monuments was opened by Black Lives Matter and activist Asa Khalif in August of 2016, when they began the call to remove the Frank Rizzo statue at Municipal Hall. Monument Lab was perfectly timed to facilitate the debate, or at least bring a wider audience into the discussion. Instead, the issue did not truly pick up steam until other cities- Charlottesville, New Orleans, and Baltimore- began to remove or relocate their monuments to the Confederacy a year later, in August 2017.

Afraid of jinxing myself, but it looks like #RizzoStatue lived to see another day and I might be able to hop on train home. pic.twitter.com/GppVN3HHfq

— Helen Ubiñas (@NotesFromHeL) August 17, 2017

I’m not certain what the issue is. Surely the topic of public monuments is big enough at this point to draw in and resonate with many, many people in the Philadelphia area- the “Live” events ought to have warranted much larger audiences. Maybe there’s a larger issue with the way the project has been managed? Maybe Philadelphians are not ready to have conversations about what monuments they do want in public yet? Or maybe the Monument Lab model is too apolitical of an approach to a deeply political problem?

[1] Taglines and mission statements sourced from the Monument Lab website

[2] Drake’s presentation can be read in its entirety on Medium.