Wartime Rationing, Food Aid, and "Civilized" Sickness: The Problem of Pellagra in 1918 (#explore1918)

Cynthia Heider | 9 May, 2018

I most recently wrote about wartime food restrictions under the #explore1918 theme in Everybody's Got to Eat! Cooking like it's 1918. Today I address a more serious side of the issue: the effect of nutritional deficiencies that could result from prolonged dependence on the type of wheatless and meatless diet that the U.S. Food Administration endorsed during World War I. Sometimes an essay topic just occurs to a writer, and other times it draws on years of stockpiled bits of research that add up to a whole. This article is the result of the latter process.

After the war, came the hunger

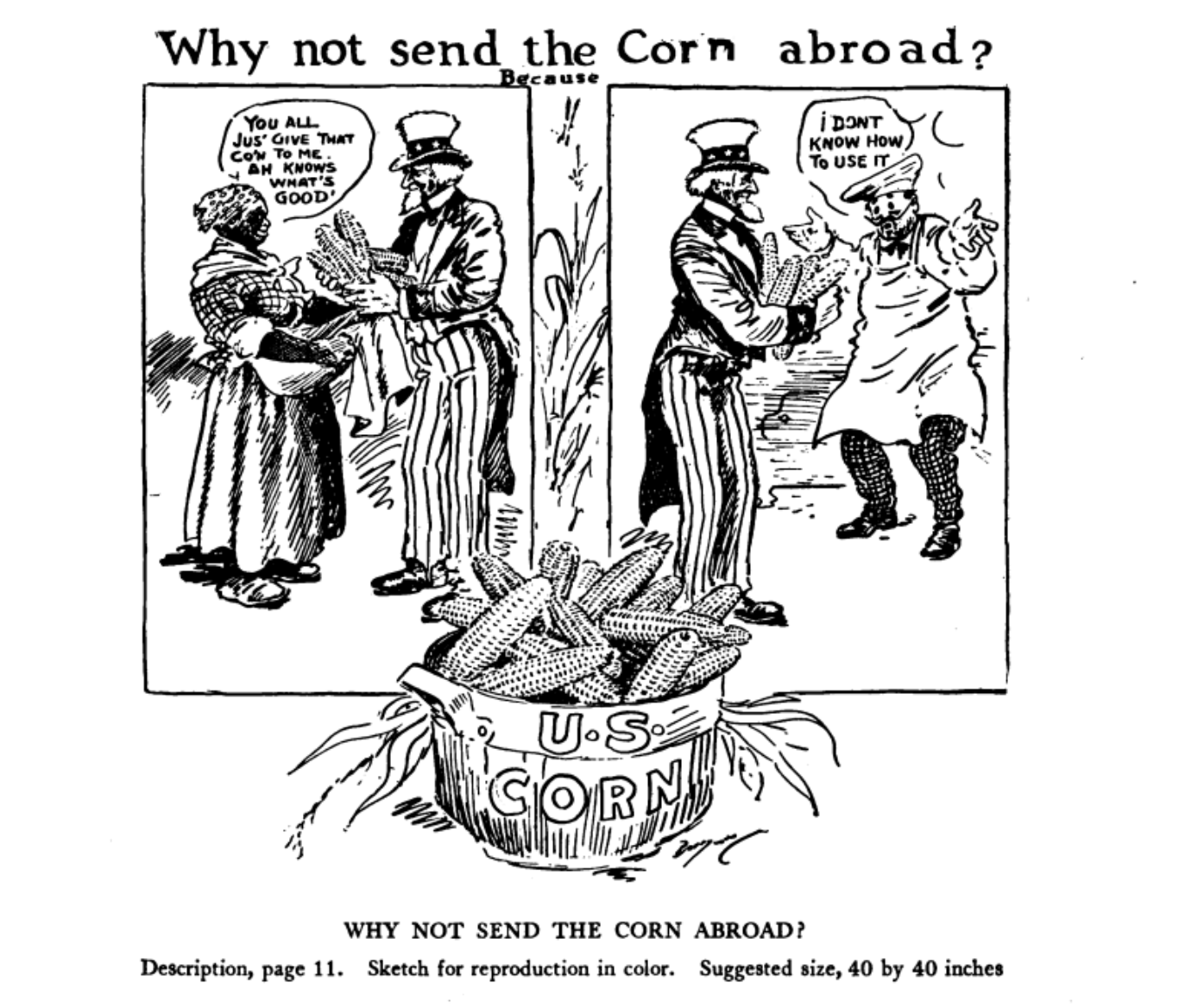

When four years of battle had destroyed Europe’s fields and crops, the Great War’s starving survivors badly needed food aid, and Americans stepped up. But what crops could they send or cultivate overseas? The obvious answer to many Americans was the plentiful resource of corn, although Europeans were hesitant to accept it. Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute invited David Fairchild (“Agricultural Explorer in Charge, Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, U.S. Department of Agriculture”) to speculate why. His answer? Pickiness. This assumption was way off.

Lazy? Picky? Snobby? Why wouldn’t Europeans eat corn?

Fairchild’s lecture on the topic, entitled “The Palate of Civilized Man and its Influence on Agriculture,” was published in the Journal of the Franklin Institute in March 1918. Reporting that even in the face of starvation, European peoples looked upon cornmeal as “chicken food,” he struggles to explain it, but can only conclude that they are fussy and traumatized, and cannot get used to eating new foods. Still, though, he reflects: “When I first heard that the Belgians refused to eat corn, and that the Irish and English would eat anything else before they would touch it, my first impulse was to insist that they ought to be made to eat it.” [1]

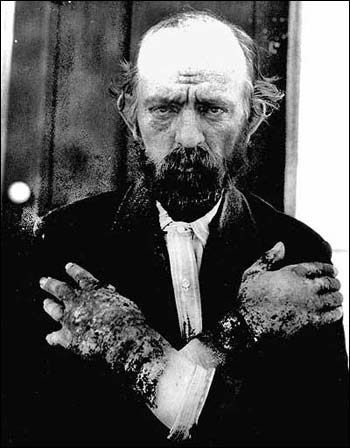

The problem of pellagra

What Fairchild didn't bother to mention was that corn-based diets had been linked to a condition called pellagra. Symptoms of pellagra include skin discoloration and lesions, diarrhea, mental and neurological issues, wasting, and eventual death. In the United States, it was mostly seen among poor Southerners; South Carolina had reported 30,000 cases of pellagra with a 40% mortality rate in 1912. [2] The situation was becoming serious enough in the United States that officials convened conferences and studies on the subject and special pellagra treatment centers were opened. A doctor at one of these facilities in Atlanta published a cautionary report on the disease's increasing frequency in 1912, warning "It would be puerile for any of our states, no matter how far north, with a 'holier than thou' attitude, to disclaim its presence, or to minimize the reality of the problem now at our doors." [3]

Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, Spanish and French scientists had investigated the cause of pellagra and determined its connection to corn, although they could not explain the exact issue. Theories varied, attributing the disease to mold or other possible toxins in corn, perhaps involving hereditary issues among the poor. Dr. Th ophile Roussel, a French physician, performed lots of studies on the disease. He then presented his findings to the French government, which took steps to decrease cultivation of corn in the country, replacing it with wheat and other cereal grains that did not correlate with pellagra. As a result, pellagra rates in the country plummeted. [4] Corn was relegated to the status of chicken feed because it was not considered fit for human consumption in Europe. In the United States, on the other hand…

When "civilization" leads to sickness

So what is corn's connection to pellagra? The issue is chemical and has to do with the way that corn is prepared for eating. At heart, pellagra is largely a result of a body's deficiency in the vital nutrients niacin (Vitamin B3) and/or tryptophan. Milling corn into meal rather than eating the kernels reduces its dietary value, and if that is a lynchpin of someone's diet, that dietary value may not be supplemented with other foods. Ironically, the American Indians who originally cultivated the crop do not suffer from pellagra because their way of preparing corn (mixing it with an alkali like woodash lye or limewater prior to eating it, a process called "nixtamalization") restores the food's niacin content. This "uncivilized" manner of making cornmeal was not adopted by colonizers in the Americas because it didn't suit the European palate.

David Fairchild assumed that Europeans' aversion to corn was irrational and ungrateful, but he came to this conclusion by ignoring the pellagra epidemic taking place in his own country. That a scientist could seriously argue this point in a lecture before a prestigious American institution indicates several things about life in 1918. Firstly, it shows the nascent stage of nutritional science at that point- for which Fairchild is not accountable, obviously. But more strikingly, it reveals the limitations of the field of scientific inquiry, where assumptions about race and class can override objective scientific analysis, even when unintentional. I wonder: How much has that changed since then?

Works Cited

- David Fairchild, “The Palate of Civilized Man and its Influence on Agriculture,” The Journal of the Franklin Institute 185, no. 3 (March 1918).

- Alan Kraut, “Dr. Joseph Goldberger and the War on Pellagra,” National Institutes of Health. Online exhibit. https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/goldberger/index.html

- George M. Niles, Pellagra: An American Problem, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1912. https://books.google.com/books?id=gC8pAAAAYAAJ.

- Richard D. Semba, “Theophile Roussel and the elimination of Pellagra from 19th century France,” Nutrition 16, Issue 3 (2000), 231-233, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0899900799002737.

This article originally appeared in a slightly different format on the Steemit platform and carried this tagline: "100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program is exploring history and empowering education. To learn more click here." It is no longer accruing Steem cryptocurrency.